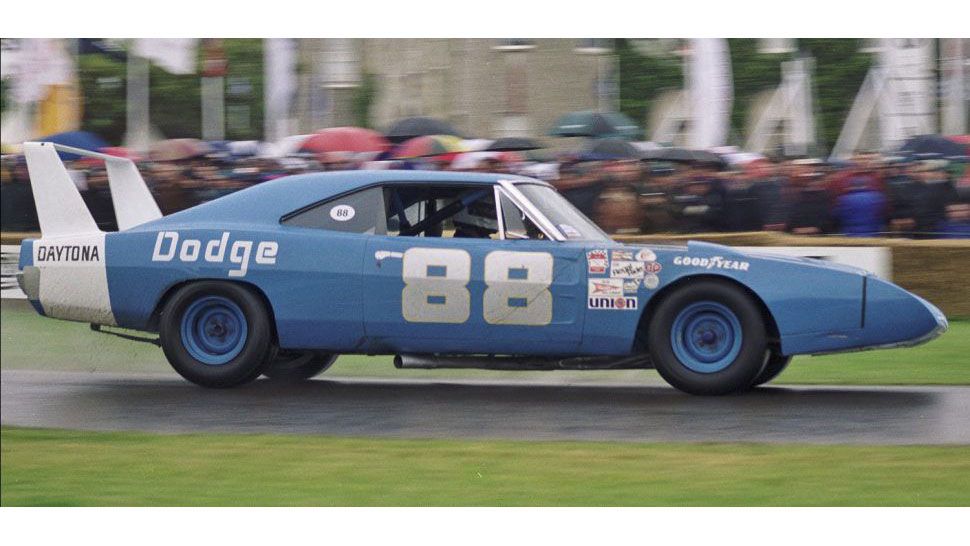

No. 88 clone at Goodwood Festival of Speed. Photo by PSParrot.

Fifty years ago, to the day, Larry Rathgeb had brought a cadre of engineers, a hired shoe, and the hottest car on the planet to Talladega. His goal: get the driver, Buddy Baker, to push the car, the Dodge Charger Daytona engineering mule, past 200 mph to set a world record. Indeed, Rathgeb and his crew did what nobody else in the world had ever done that day. Rathgeb, however, won’t be able to celebrate today’s anniversary of the event; he died Sunday at the age of 90, reportedly after contracting the coronavirus.

Rathgeb, who started his career as an engineer with Chrysler, by the mid-Sixties rose to become the lead engineer for racing development in the country. In that role, he not only worked with the teams running Chrysler products in stock car racing (“Rathgeb even lived with the K&K racing team for a period of time, sleeping in a trailer out behind (Harry) Hyde’s shop in Charlotte,” according to Steve Lehto’s Dodge Daytona and Plymouth Superbird: Design, Development, Production and Competition.), he also had a hand in developing the Dodge Charger Daytona with its tall wing and extended nosecone.

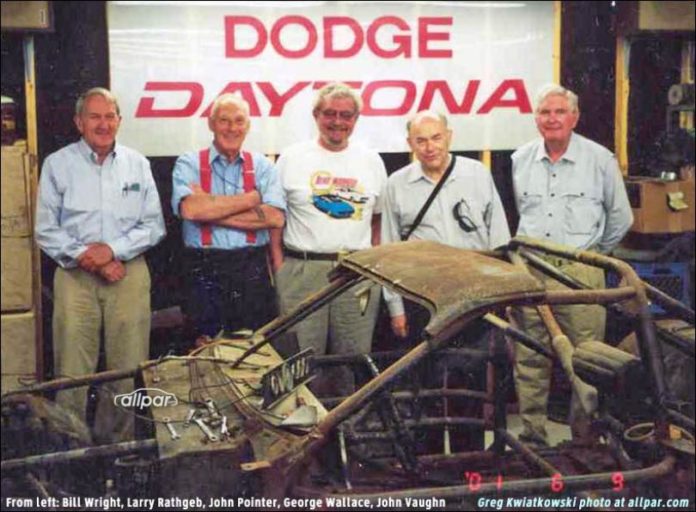

Any one of those Daytonas would have defined Rathgeb’s career at Chrysler, but one in particular ended up his crowning achievement. Ironically, as Allpar noted, it was an impound-lot refugee that had nearly been abandoned. As the story goes, a Hemi-powered Charger press car loaned out to a car magazine in Southern California ended up stolen, stripped, and left on a Watts street on cinder blocks. Rather than leave it out there, Chrysler decided to bring it back and hand it off to engineering to use as a mule.

Rathgeb, in turn, used it to test-fit the bodywork changes that John Pointer and Bob Marcel suggested, modifications that would make the Daytona out of the Charger 500. According to contemporary estimates, the aero mods should have helped the car cheat the wind up to 220 mph, supposedly impossible given the tracks NASCAR raced on at the time. However, Rathgeb brought in some professional drivers to do some test runs at the Chrysler Proving Grounds in Chelsea, Michigan, where Baker reportedly ran the mule up to 235 mph and Charlie Glotzbach took it to 240 mph.

Rathgeb (right) with Chrysler Engineering race mechanics Fred Schrandt (left) and Larry Knowlton (center).

Those sorts of results led Rathgeb to convince Ronney Householder, his manager at Chrysler, to permit the mule to qualify for the Talladega race in September 1969. With Glotzbach at the wheel, the mule, which Ray Nichels had entered as number 88, turned in a pair of 199-plus mph laps. The driver walkout at that race kept the No. 88 on the sidelines – a sister car won the race with a substitute driver at the wheel – and Rathgeb famously thought his career at Chrysler over, if only because he promised Householder the engineering mule wouldn’t exceed 185 mph.

According to one account of the episode,

Back in Highland Park, Rathgeb was on his “last walk.” This was not good. “I was grateful and privileged to work for Chrysler,” he said. It would be a disaster to lose his job. His boss, Dean Engle saw him on his way out of the race engineering office and said he would go along. When they arrived at (Chief Engineer Bob) Rodger’s office, Engle spoke up, as Rathgeb remembers. “He said, ‘I want to make a comment. The purpose of racing is to, number one, get the pole, and, number two, get the win.’ Bob Rodger looked at House and said, ‘Well?’ There was no response. Then Rodger said, ‘I think that in the future we should communicate better.’” The meeting was over. Rathgeb got his reprieve. Life could go on for a while longer—and it would get a lot better for both Rathgeb and Dodge.

Indeed, a few months later, Dodge PR Director Frank Wylie wanted to see if the Daytona could actually break 200 mph in a public demonstration of its capabilities. Rathgeb once again called in Baker, prepared the engineering mule, still wearing No. 88, and flew down to Talladega in March 1970. When asked, he and his crew said they were there for transmission testing.

It took 30 laps and multiple adjustments of the car, but Baker finally broke the 200 mph mark that afternoon, running 200.447 mph, becoming the first person in the world to lap a closed-circuit track at that speed. At the time, as Preston Lerner wrote for Motorsport magazine, “the lap record in Formula One stood at a relatively paltry 152 mph. At Indianapolis, it was a tick more than 171 mph.”

(Side note: The No. 88, long thought to be the one the International Motor Sports Hall of Fame in Talladega had on display, has since been located and gone under restoration.)

Nor was that record Rathgeb’s only major contribution to stock car racing. After Chrysler folded its NASCAR program in 1972, Rathgeb went to work on a short track race car that customers could buy from Chrysler either in pieces or as a whole – a kit race car, in essence, built up from E-body front components and A-body rear components.

While testing the car, Rathgeb needed a driver who knew dirt tracks, and Hyde recommended an up-and-coming driver who needed the money, Dale Earnhardt. As the story goes, Rathgeb was impressed by Earnhardt’s skills and, when Earnhardt confided in Rathgeb that he might give up on stock car racing because times were getting tough, Rathgeb convinced Earnhardt to keep racing.

Rathgeb remained with Chrysler at least into the late 1980s and attended Chrysler reunion events as late as last October. According to a report on Allpar from fellow Chrysler employee Bill Adams, Rathgeb contracted the COVID-19 novel coronavirus at a senior independent living community in West Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. His family is reportedly waiting for the pandemic to subside to schedule a memorial service.